Kruakae Pothong and Sonia Livingstone

The Digital Futures Commission is about to launch yet another flagship toolkit to guide digital innovation towards Child Rights by Design at the end of March 2023, building on Playful by Design and recognising the vast array of digital products and services that impact children’s lives.

Recognising that innovators find designing for children challenging, we consulted children about their experiences and expectations of their rights in the digital environment when building our Child Rights by Design toolkit.

Consulting children about their rights in the digital environment

We consulted 143 children aged 7 to 14 through in-person workshops in four schools across different cities around the UK in July 2022. Our workshops included a relatively equal mix between girls and boys from diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds. The workshops aimed to understand:

- Children’s understanding of their rights

- How do they reflect on their rights concerning the digital products and services they use

- The changes to design features and digital functionalities that children expect to see.

To ensure complete coverage of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), we synthesised the 54 Articles of UNCRC into 11 child rights principles. These provided the basic structure of our children’s consultation.

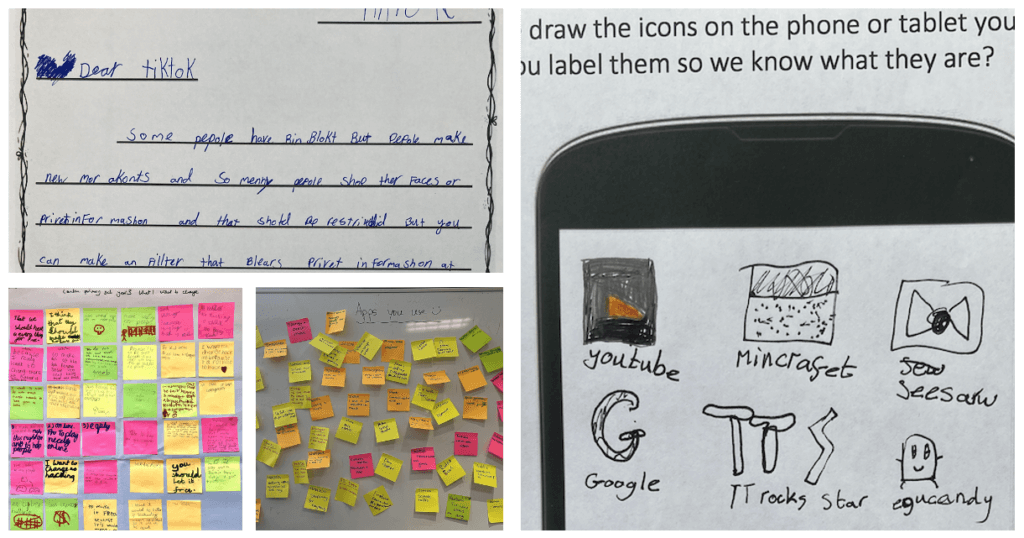

Being sensitive to children’s evolving capacities, their playful nature and story-based communication, we devised a range of dynamic activities for the consultation methodology, including drawing, letters to the app boss and post-its (for short comments) mixed with discussions and reflections. These are explained in our methodology report, Children’s Rights through Children’s Eyes.

What does a child rights-respecting digital world look like to children?

Children could not be clearer that they long for a child rights-respecting digital world. They understood all our 11 child rights principles and were keen to explain how they experienced these principles and what they wanted to change.

They told us they did not appreciate the current arrangement exploiting their interests and attention. They want to exercise their agency rather than being manipulated into signing up for a deal they could not even bargain for.

“I think they just use you. For example, when you’re playing a game and it says it’s free, and then you press it and then it’s like, you have to put your bank details in it.” (Year 4, Greater London)

Children expect the digital world to treat them fairly and be inclusive by providing more accessibility features and addressing cost barriers.

“Please [do] not make apps so expensive because people can’t all buy the app they want, and the app workers can’t make much money.” (Year 3, Greater London)

Children also expect the digital world to put their best interests at least on par with business interests.

“It’s [the app is] made in a way that it is for me, as well as being they want loads of money” (Year 8, Essex)

“I wish the world wasn’t money hungry, and they purely made apps and games for entertainment only. Listen to people’s thoughts.” (Year 9, Essex)

Children care about their right to privacy and data protection. They expect the processing and usage of their data to be proportionate and purpose-specific.

“When you download a game, it says, can this game access your files? Then it’s, why do you want to see what my files are? That’s in my bad interest because I don’t want it going through my files, thank you very much.” (Year 8, Essex)

This expectation is consistent with what the law (UK GDPR) says. But, implicitly, this request also shows that children also expect businesses to be responsible by complying with relevant laws.

Children demand to be consulted and have their views taken seriously. They are unhappy with the current arrangement in which many adult innovators appear dismissive of their voices.

“We have the right to speak up, and people should listen.” (Year 7, Yorkshire)

Children want to feel safe online and be offered age-appropriate experiences.

“All ages should be protected, not just certain ages.” (Year 9, Yorkshire)

“Valorant, the game where you can play with 50-year-olds…Because of the way that you play it, guns shooting at people to win, … it’s rated at 16. But you can turn those stuff off in your settings…you can turn off the explicit words in chat and in other places. So, I don’t understand why it should be a 16.” (Year 9, Essex)

They want to express themselves and participate in the vibrant digital world though that is not always possible online.

“Sometimes social media can make you feel like you can’t be you. You have to be someone else and be like other people.” (Year 7, Yorkshire)

Children definitely enjoy and want to enjoy more creative and development opportunities and other activities that enhance their wellbeing.

“Can you make more apps based on Toca World? Because it is so creative for lots of children – so they can do something creative instead of watching something.” (Year 3, Greater London)

“When it comes to Yousician, it can go at your own pace, and I can do what I want. If I want to learn shredding, which is something you play really fast on guitar, I can start learning that straight away.” (Year 9, Essex)

Integrating children’s views into our guidance for innovators

Children’s understanding of the 11 child rights principles guided our interpretation of these principles and their relevance to children’s lives and concerns – in their own words – in the development of the Child Rights by Design toolkit. We also included direct quotations of children’s descriptions of specific digital features and functionalities that they deemed to hinder or enhance a particular principle in the design cases. In this way, we bridged children’s views and the perspective of the digital innovators who will use the toolkit. For example, here’s a request for change from a child participant that articulates how the delivery of age-appropriate digital experiences can be improved:

“I believe that age restrictions should become harder to bypass as I see many young children below the age of 12. You also should look into higher censorship as there have been many events in the past of extremely gruesome clips: a guy shooting himself, a guy getting hit… and children playing with guns.” (Year 8, Essex)

We further synthesised what children identified as enablers and barriers to their enjoyment of their rights in the digital environment into design considerations through prompt questions to stimulate designers’ reflections. In short, by incorporating children’s voices from our consultation in our description of our child rights principles, design examples and prompt questions, children’s experiences and perspectives informed our guidance for innovators – the Child Rights by Design toolkit.

This will be launched at the end of March. In this way, children’s voices and rights stand a better chance of being factored into the digital products and services they use by design.