By Kruakae Pothong and Sonia Livingstone

Just before the summer break, the Digital Futures Commission went to schools! We wished to consult children about how they experience their rights while using digital products and services. This work was designed to inform our work stream on Guidance for Innovators, building on our Playful by Design principles and prior consultation with children, to advance a vision of Child Rights by Design.

Listening to children is vital to our work at the Digital Futures Commission, extending the insights from our earlier mapping of children’s voices on all things digital. General Comment 25 states that children’s rights apply equally in both physical and digital environments, and these rights include children’s right to be heard in matters that affect them (Article 12, United Nations on the Rights of the child (UNCRC)).

In July, we held 20 workshops with 143 children aged 8 – 14 years old in four schools in different cities around the country. Our workshops included girls and boys from diverse cultural and ethnic backgrounds. We learned a lot from the children’s enthusiasm in talking about their rights, whether these rights are respected online, and what needs to change.

Consultation design

Aware that human rights are rather abstract, we prepared fun activities tailored to children’s curiosity, playfulness and ways of expressing themselves. In this way, we could ensure that the different rights we asked about – best interests, non-discrimination, privacy, development and so on – were accessible and tangible for children.

To capture the range of rights, we adapted the widely used grouping of the 54 Articles of the UNCRC for states’ reporting requirements to distil a set of key principles. We then devised prompt questions and activities to support children in articulating their understanding of these principles and relate them to their digital experiences.

We wanted to know:

- What digital products and services (apps) children use and why

- How children perceive their rights in relation to the apps they use

- What changes they want to see in these apps, especially as regards digital design features

We used a parent/child consent process developed earlier to explain our work and research ethics procedures. Our moderators had passed the disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) check, and a teacher was present in each workshop.

A fun-filled consultation

Each workshop took up to an hour, with some activities for larger groups, some for smaller groups and some individual activities in the mix.

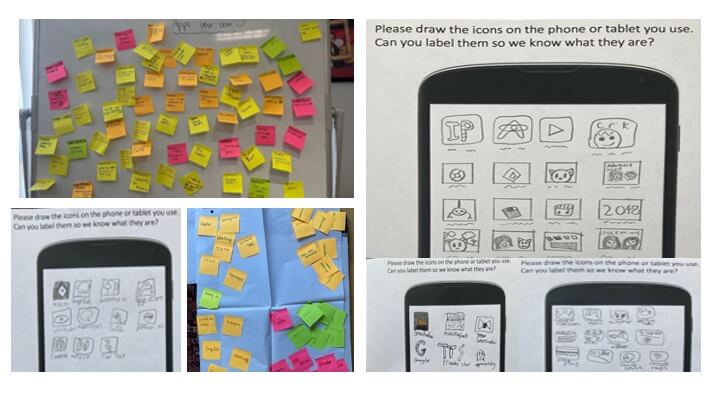

After introducing ourselves and the workshop aims and process, we invited primary school children to draw the apps they use onto an outline of a mobile phone, and we asked secondary school participants to write the name of each app they use on a post-it and put their post-its on a poster or wall.

Our sensitivity to children’s playfulness and love of creative tasks paid off as drawing or scribbling down the name of apps on post-its and seeing what others had contributed got everyone relaxed and talking. These warm-up activities allowed us to tackle our main challenge: to discover how children understand their rights and how they experience their rights when they use these apps.

We built on the momentum of children’s keen interest in technologies and their critique of the apps they use by asking them for examples of the apps they think are good and bad for each of the child rights principles we distilled from the UNCRC. For example, in relation to the principle of participation, we asked prompt questions such as:

- What comes to mind when I say participation? What does it mean to participate?

- Now, think about the apps that you use. Let’s look at all the post-its on the wall. Which apps are really good for participating? Why? What makes them so good for participating?

- Now think about the apps that are not so good for participation. Why? What makes them bad for participation? What is missing in this app? How does it not support participation?

- We also asked some more directive prompts to follow up, such as: should people be able to say anything they want to say online? If you want to make a difference in the world, do you think any app can help do that?

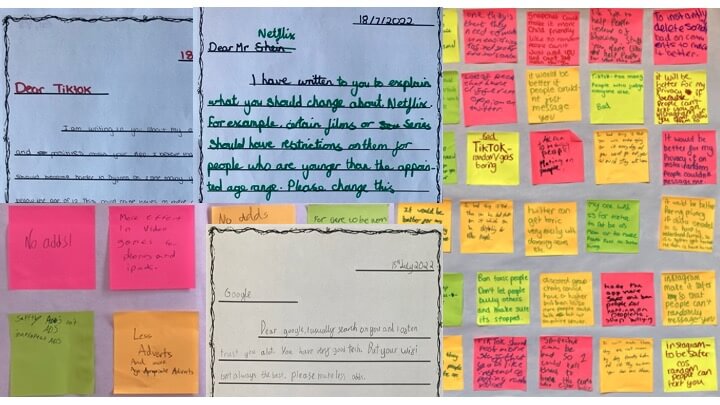

- “Shorter [and] simpler” terms of use to ensure that young people understand what they sign up for and “no ads” (year 8)

Many, particularly younger participants, are keen to see a digital world that offers greater opportunities in support of their creativity, development and growth, thus calling for more diverse and creative activities, particularly in games, to avoid being “repetitive [which makes them] boring” (Year 5).

Children are also sensitive to various forms of commercial exploitation and keen for their views to be heard on how digital industries should operate: “I wish the world wasn’t money hungry, and they purely made apps and games for entertainment only. Listen to people’s thoughts?” (Year 9).

They value other rights too:

“Do not add chat censors as it is in our digital rights to have freedom of speech.”

Year 8

“[Include] more [people] who aren’t include that much like disabled people in games, moveies”

Year 7

We believe that technologies should serve users, including children, and facilitate human flourishing rather than harm them. So, we will build on the insights from children, their understanding of their rights and their expectations of how their rights should be reflected in the digital environment in constructing our guidance for digital innovators. Stay tuned!