By Kruakae Pothong and Sonia Livingstone

The internet has become a lifeline for both adults and children during COVID-19 lockdown for work, education and fun. Ofcom research shows that children are spending even longer online for play, study and social connection. The prominence of digital media in all our lives, especially when in-person social interaction is limited, makes the Digital Futures Commission’s agenda to reimagine a better digital world even more critical and timely.

Researchers, too, have had to adjust to working online. So how do we ethically consult children, young people and the general public on a platform like Zoom? In this blog, we share what we have learned of the tricky issues to be addressed during our public consultation on play in a digital world.

Before launching the consultation, we learned from our prior and ongoing research:

- our Children and Young People’s Voices report, which highlights what children and young people value about the digital world and the changes they want to happen;

- our Panorama of Play report, which sets out why free play matters, including in a digital world;

- our Kaleidoscope of Play in a Digital World report (forthcoming), which critically reviews current research on play in the digital environment;

- our Child Rights Impact Assessment report, which shows how and why children’s rights should be embedded in digital design and policy innovation from the outset.

A public consultation on play must be rights-respecting, ethical and evidence-based, building on what children told researchers in prior consultations and available research; it could even be playful! To explore children’s opportunities in the digital environment and figure out how play can be better enabled, we invited views from UK children and young people, parents/ carers, and professionals who work with children.

Participant recruitment

COVID-19 challenged our usual ways of recruiting participants – schools were too busy to help us while parents were frazzled with home-schooling, and young people were already ‘Zoomed out’ by the second lockdown. We worked hard to partner with some great intermediaries, including our Commissioner organisations, youth groups, parent groups, and others keen to support the consultation, recognising how much play opportunities matter during the pandemic.

Group composition

Whereas traditional focus group discussions tend to include 6-10 participants, usually demographically similar (children, or parents, or professionals), we allowed more spontaneous group construction. For example, a group of young people joined with professionals working with them; sometimes, we included family groups (one or two parents and their children) or bring parents together or mix parents with professionals in a discussion. On Zoom, we also learned that a group of 3-5 is optimal and that bigger groups should be broken up for everyone to have a chance to talk.

Informed consent

Previously, we might have emailed information and consent forms to teachers to distribute to children or given participants printed consent forms for them to sign in person before the consultation. But during the lockdown, this process proved off-putting for potential participants, not all of whom had a computer, printer and scanner. To obtain parent and child consent, we needed to develop a process that was inclusive and easy to manage on the phone. We developed a straightforward email process to ensure comprehension and reduce friction. On occasion, we permitted some participants (e.g. adults; children joining our consultation with a parent or carer, a few teens for whom parental consent had been obtained, separately, before they joined the consultation) to audio record their consent at the start (after a reminder of our research ethics process – confidentiality, anonymity, their right to disengage without consequences, and so forth). The LSE Research Ethics Committee commended our email consent process as best practice.

Group discussion design

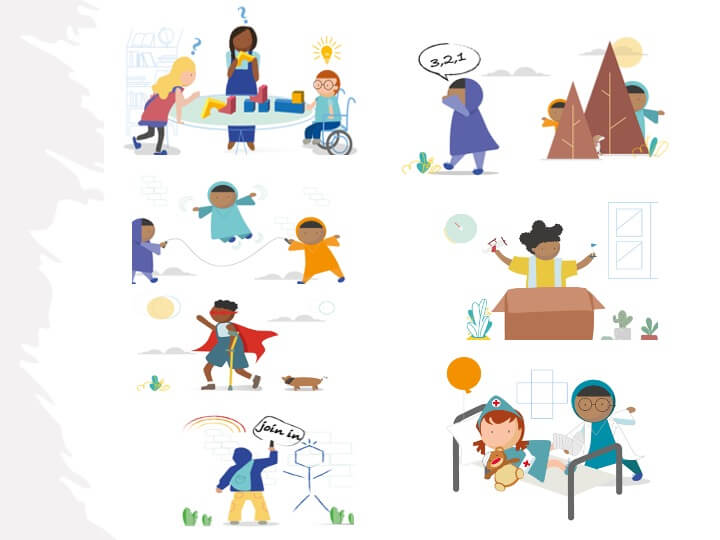

We structured our topic guide into three sections: i) Ice-breaking, ii) experience sharing and iii) envisioning future play in a digital world, including direct questions on the changes that participants want to see in the digital environment. Given Zoom fatigue, and screen fatigue in general, and the stresses of COVID-19, we kept the interviews within 45-55 minutes. Noting the challenge of engaging participants of various ages and with different experiences of play in critical conversations about diverse qualities of play, we used cultural probes1 in the second section to build on free play concepts in general and elicit their expectations about playful opportunities in the digital environment. We challenged participants’ familiarity with digital play by asking them to map the qualities of play in the illustrations onto the digital environment. This exercise encouraged reflection and critical discussion about how digital features afford or undermine certain qualities of play.2

Zoom handling

Although Zoom creates both audio and video records of the discussion, we committed to participants to delete the video and retain only the audio recording for transcription and analysis out of respect for their privacy. Occasionally, this meant taking notes on how children made funny faces or pointed at objects around them to make sense later of what was said. We did not create breakout rooms for separate discussion for ethical reasons unless we (having passed the UK Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) check) could each moderate a breakout room. We only give participants a fresh consultation Zoom link and password for each consultation session after they confirmed their attendance for safety and security reasons. We also noted the importance of turning off the direct messaging mode in discussions with children and young people via Zoom.

Constructing a vision of play in a digital world

Our consultation has now finished, gathering input from 126 participants, half of them children, the other half parents, carers and professionals. We have used the coding software NVivo to analyse what they said and reveal their views and expectations of free play in non-digital and digital contexts. Next, we will develop a vision of play in the digital environment by mapping the features and resources participants identified as supportive of their positive, playful experience with the qualities of play identified in the Panorama of Play and the evidence reviewed in our forthcoming Kaleidoscope of Play in a Digital World.

Notes:

[1] Cultural probes are evocative exemplars or open-ended activities often used in design or research to encourage participants to talk freely about their experiences, values and design ideas).

[2] We worked with our colleagues in BBC R&D to brainstorm ideas and generate the illustrations (cultural probes) of play activities that reflect the eight qualities of free play identified in our Panorama of play report.

[3] Additional resources on meaningful engagement with children include:

- Engaging children and young people in research online (CO:RE: Children Online – Research and Evidence)

- Child participation guidelines for online discussions with children (Child Rights Coalition Asia)

- Youth participation in a digital world (Berkman Klein Center, Harvard University)

- Child participation assessment tool (Council of Europe)

This blog is part of the play series. You can view the rest of the blog series here.

Professor Sonia Livingstone OBE is a member of the UNCRC General Comment’s Steering Group, and leads the Digital Futures Commission. Sonia is Professor of Social Psychology in the Department of Media and Communications at the London School of Economics and Political Science. She has published twenty books on media audiences, media literacy, and media regulation, with a particular focus on the opportunities and risks of digital media for children and young people.

Dr Kruakae Pothong is a researcher at 5Rights and visiting research fellow in the Department of Media and Communications at London School of Economics and Political Science. Her current research focuses on child-centred design for digital services and children’s education data. Her broader research interests span the areas of human-computer interaction, digital ethics, data protection, Internet and other related policies.