What is the potential, and the problem, with digital design? How can we make digital design more compatible with children’s evolving capacities? In search of answers, Sonia Livingstone and Kruakae Pothong talk to Jenny Radesky about digital design and its implications for children’s development.

Kruakae: Our current work on play aims to change the black and white thinking about play (not just gaming) in the digital environment. So, we ask: What does good look like?

Jenny: I am interested in how the design affordances of mobility and interactivity affect interpersonal interactions because a lot of my clinical training emphasizes the importance of early parent-child relationships, attachment and resilience in the context of toxic stress.

In my research interviews, parents talked about their own inner experiences using mobile tech around kids. And a lot of them talked about design features. They talked about notifications, rewards, and other persuasive design impacting how attached they felt to their devices – and how exciting yet exhausting it felt to be splitting their attention between parenting and technology. So I became interested in how persuasive design can either support or undermine parents’ and children’s daily experiences.

Building upon the research on dark patterns in video game design, we’ve been trying to see, where is persuasive design crossing the line with children? Where is it becoming a design abuse? Where is it limiting user agency? Where is it tricking the user? Where is it putting undue pressure that’s not appropriate for a child’s developmental needs?

Sonia: So, you have moved, in a way, from thinking about how to illuminate parents’ understanding to thinking about the policy. Are you talking to designers, working with designers?

Jenny: One project I’m working on is about the design cues or surface cues that help children understand what’s going on behind the scenes – for example, with data collection and privacy. We interviewed five to ten-year-olds, and many of them spontaneously talked about surface cues on YouTube, or their favourite game, or Netflix, that gave them hints about where the data were stored and what was happening behind the scenes. Although they got some things right, they would often erroneously point to the history section of the user interface (UI) and say all their data was stored there. So, we thought there is the potential for designers to create micro-interactions or surface cues that let children know when things are going back to headquarters, not being stored locally, and when their data is being processed.

Sonia: Absolutely. Another thing we’re thinking about is where there are possibilities for different business models.

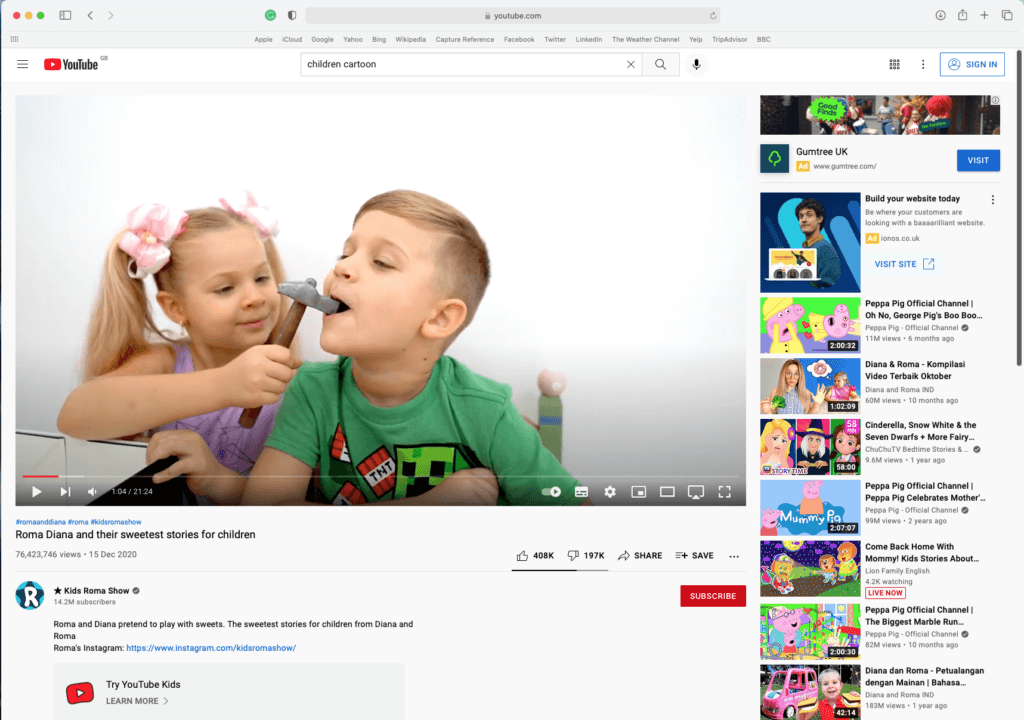

Jenny: Ad-based business models aren’t always being executed in a child-centred way. My lab has reviewed hundreds of children’s apps and YouTube videos, and we keep seeing sloppy ad practices. Developers and platforms seem like they are just taking it for granted that these are sustainable possible business models, but they are so disruptive to children’s digital experiences. For example, in our Common Sense Media report, we found that kids’ nursery rhyme videos on YouTube had the highest frequency of ads compared to other genres. We counted the number of ads that show up on the top ten YouTube child-directed channels, and some of them run for longer than the video itself. About one in 5 ads on child videos were age-inappropriate – we suppose that ads are sneaking through that probably labelled themselves as child friendly, but they’re for dodgy video game websites.

Sonia: And not to mention programmes that are really ads.

Jenny: Yes, which make up a lot of the top viewed videos. How are we going to change this ecosystem without there being alternative sustainable business models, that actually could be even more lucrative because they truly are serving what children and families need? And are not just subscription models used by white, wealthy families?

Kruakae: So, what is your hope? You advocate transparency in digital design. What do you expect kids and/or parents to be able to do with that transparency, realistically?

Jenny: For one thing, we know that children are making guesses about how their data are handled based on the user interface – so, the more honest and accurate those interfaces are, and the less they obscure what they are doing, the more accurate kids’ informal inferences will be. Children are always looking for cues in the environment for how things work.

But, I think it’s not only transparency. Maybe it’s also just a bit more of choice or agency provided in the user interface. If you are a parent trying to manage your child’s YouTube, one of the key frustrations I’ve heard has been about children being distracted during remote learning and being led down algorithmic feeds into territory neither the child nor parent really hoped for.

Although YouTube is a potential place for cool and creative content, its recommendations feed elevates the clickbait and trending content. If a child starts on a video that is not ‘made for kids’ – which channels may not want to identify as because it limits behavioural advertising – then the recommendations feed is likely to offer trending not-for-kids content. I would love for YouTube to offer parents and children the option of not having a recommendation feed, or just a limited set of new channels to discover that have been vetted for positive, creative content.

Kruakae: The other approach you had talked about is elevating the good content. What would be the interest for platforms like YouTube to, say, prioritise more content from Sesame Street rather than any other stuff.

Jenny: Yes. I think the incentive for YouTube would be to prevent families from leaving the site wholesale if they see YouTube as not child friendly at all.

It’s not that it needs to be some sort of social engineering to make sure every child watches Sesame Street and Berenstain Bears and other positive [content] that have been constructed to try to teach through storytelling. But at least, don’t take them down the opposite path – to video after video of unboxing videos or consumerist, wish-fulfilling vicarious vlogs that offer minimal storytelling or meaning-making – other than norm generation around consumption and excess.

In order to elevate educational and meaningful content, metrics of video success will need to change. Currently, the metric is engagement: how many likes, comments, subscribers (which lots of YouTubers actively ask kids to do during their videos – it’s a bit shameless). What if the metric was how likely the parent and child were to have an interesting conversation about the video? How much the child learned a cool idea that launched a subsequent activity in their physical or social world – like Curious George episodes try to do? I realize this would lead to more children shifting their attention off of YouTube, and on to other activities, but it is an example of changing the design to suit the child’s best interests rather than the interest of ad impressions.

Sonia: We did a consultation with kids and parents, and one thing that they said to us loud and clear was they wanted more digital content that they could take into their world and build hybrid play spaces and opportunities. Then I read about the metaverse, and I think, okay, so the game if designed well, if they’re going to build that, that’s great, but of course they’re only going to build it if they can monetise it… Whatever new kind of avenue you open up, with the most public-spirited and child-centred vision, is grist to the mill of this astonishingly creative business.

Jenny: Yes, I do worry about how newer and more virtual spaces will be monetized more rapidly than we can provide guidance for how families can navigate them. Proactive design codes like the UK’s will hopefully address this through child impact assessments, but I also sometimes want to bury my head in the sand and just keep my kids out of these spaces for fear that their interests will not be considered – which I know is just going back to the screen time model of “just say no!” But it helps you understand why such a reactive stance has been taken by child advocates.

Sonia: We talked to the kids during the worst moment of lockdown, really. So, they talked about playing online with a lot of pleasure of, that’s where I can be creative. That’s where I can meet my friends and, as Mimi Ito would say, hang out and mess around. I do feel we should be saying, those are the spaces to build, but they should allow for the kind of flexibility and adaptability that you were talking about.

Jenny: I agree. In our review of apps labelled as “educational” we found that most designs are pretty closed-loop, constrained sets of activities that don’t provide much exploration or autonomy.

Another issue is I’ve asked some of my lower income patients, the parents, have you tried YouTube Kids? And they [responded] what is that? So, they don’t know. This was before YouTube started putting the YouTube Kids link under every kid-directed video. Once the habit of main YouTube was established, it was hard to transfer kids to YouTube Kids.

Sonia: Maybe there is something interesting to say not only to designers, but also to content producers, that somehow they’re underestimating kids and what they make is a bit too safe and a bit too dull and should be a bit edgier, but without going over the edge.

Jenny: That’s interesting. I do think it’s an issue of really being creative about content creation and not just following little kiddie scripts or copying whatever challenge is trending. There is a content desert for elementary school age and middle childhood, and finding a balance between edginess and depth is important. My kids have been reading a lot of comics, and I think that graphic novels are pushing that edge right now, where they have such fun, interesting content, but a bit more drama that attracts child readers, yet a lot of care is given to developing rich characters and storylines that resonate with their stage of life.

Whereas the rapid “get to scale, push out stuff” approach to content creation on YouTube and other platforms – it’s thin and not well produced and potentially carrying a lot of stereotypes. In our reviews of YouTube content, we have wondered how much thought is going into producing these videos, to writing a script? Is thought given to what messages are children going to take away from this? Is it going to carry forward tropes that we’ve been trying to get rid of in mainstream media? All that stuff has the potential to come back.

I realize I am sounding quite critical of children’s digital spaces right now, but I hope that platforms and tech companies are going to be responsive to some feedback on child-centred design principles. If child-centred researchers go into these digital spaces and find problems, find design features that are clearly crossing a line with children, it would be great to have a constructive conversation about what can be done to improve it. I know there are fixes. This would not only improve children’s digital experiences but also take away a lot of the panic about children’s screen use and allow a more practical conversation.

Assistant Professor Jenny Radesky, University of Michigan Medical School: My research focuses on the intersection between mobile technology, parenting, parent-child interaction, and child development of processes such as executive functioning, self-regulation, and social-emotional well-being. Our projects use a combination of methods including surveys, videotaped parent-child interaction tasks, time diaries, and mobile device app logging to examine how parents and young children use mobile technologies throughout their day. We have developed novel content analysis approaches to understand the experience of young children while using commercially available mobile apps – including advertising content, educational quality, and data collection. We emphasize questions that are relevant to everyday parenting experiences, and also consider what design changes would help create an optimal default environment for children and families.