By Kruakae Pothong & Sonia Livingstone

This is the question that gets us up in the morning, though it’s not easy to answer. We are living through an unprecedented debate over the ethics and human rights principles that could or should underpin digital innovation. Faced with a bewildering array of new policy documents – guidance, codes, standards and proposed legislation – how can one work out what’s best, what’s feasible and what will advance children’s best interests?

At the Digital Futures Commission we’ve been reviewing these policies to complete one of our missions: developing guidance on designing for child rights by learning from today’s lively debate over what needs to change. Can we create an equivalent of a surgeon’s check list for designing for children’s rights? This could be a nifty way of making child rights impact assessment accessible and actionable, so children’s need are anticipated during the process of digital design and product development rather than being an afterthought!

Our journey so far

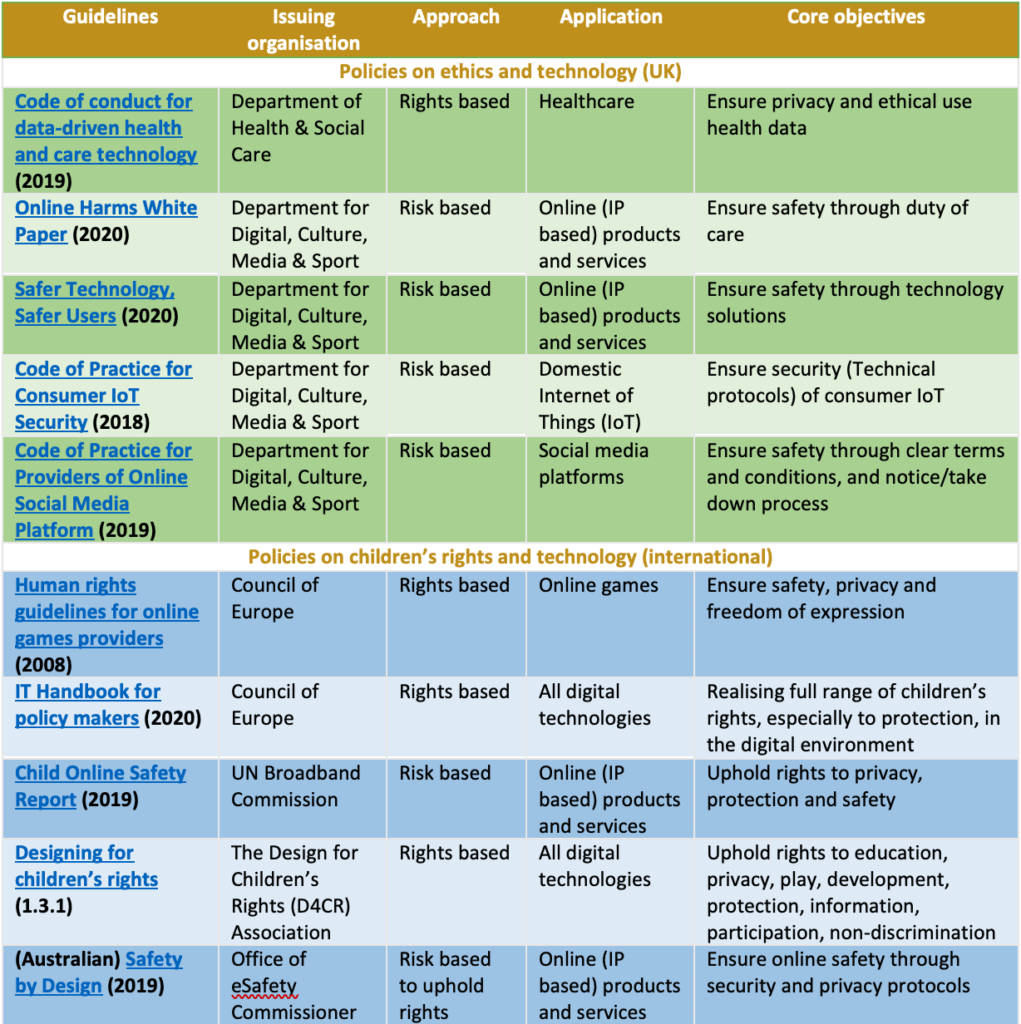

Crossing our desks and our inboxes each day are two main kinds of policies – those intended to make digital technologies (including the organisations that provide them and the manner of their use) more ethical for society as a whole; and those focused on ensuring that digital technology respects children’s rights in particular. There are many more of the former, so although our concern is with the latter, we will cull the best ideas wherever they arise (even if, as generalist proposals, they may make little or no mention of children).

We have identified nearly 100 promising policy documents (including guidelines, industry standards and regulations) from many parts of the world. Here we compare examples from two groups of policies for thematic analysis, namely those concerned with:

- Ethics (including values, trust and human rights) and technology

- Children’s rights and technology

We ask: will policies to make digital technologies more ethical (i.e., “good” for society in general) sufficiently benefit children or are more specific policies needed to embed children’s rights in relation to the digital environment?

What does “good” look like?

Our #DigitalFutures work is UK-centred, so it first struck us that UK policies position society as a whole as the primary beneficiary, while specialist policies on children’s rights tends to be more regional or international. While this may be an accident of our selection, it makes us wonder if there is already a challenge in bringing a child rights lens into UK debates over ethical tech.

Perhaps this would not matter if the emerging consensus as to “what good looks like” for technology in society is sufficient for all. Certainly, we can see that some important issues are common to many of these policies:

- Protect and respect individuals’ privacy

- Ensure security of devices and systems

- Encourage ethical business practices

- Ensure safety of users

Differences between policies for children’s rights and for society as a whole

We also find some interesting differences in emphasis between policies to make tech better for society and those centred on children’s rights, as shown in the Table.

- Policies concerned with children’s rights and technology focus more on realising a wider spectrum of human rights in the digital environment. By contrast, policies on ethics and technology tend to target particular issues (e.g., security, safety, privacy).

- This in turn seems to be because the policies on ethics and technology that we have considered take a risk-based and apply to specific domains (e.g., healthcare, social media). Hence policies on children and technology appear more holistic in scope and application.

- Being primarily motivated to reduce risk, policies on ethics and technology emphasise making digital technologies more reliable and trustworthy for the general public; this is a very different motivation from the effort to advance human or, indeed, children’s rights, although their practical consequences then may be similar in some respects (e.g., promoting privacy via data protection regulation or requiring user safety).

- The holism or breadth in approach of child rights’ policies highlights the challenge of balancing rights – for example protection vs participation or privacy. In the language of children’s rights, this means finding accountable mechanisms to determine children’s best interests. Interestingly, such challenges also arise in the wider society, for example when risk-focused policies are found to clash with, say, policies on free expression. It seems to us preferable to address them within the scope of a policy rather than leaving them to emerge later.

So, “good for children” and “good for society” are not quite the same

At this point in our work, we conclude that the changes need to ensure that digital technologies are “good for society” do not encompass the full spectrum of what makes digital technologies “good for children”. This is especially the case for children’s rights to provision and participation, but it also matters for their rights to protection given that only with a holistic assessment of likely impacts on children can one properly weigh the risks and benefits of particular policy interventions.

Our work to develop practical guidance to inspire digital innovators to embed children’s rights into their products and services from their inception is ongoing. We invite views and recommendations on relevant guidance that we can build on developing child rights-respecting guidance that speaks to policymakers, designers and businesses.

This blog is part of the innovation series. You can view the rest of the blog series here.