By Sonia Livingstone and Kruakae Pothong

Can we imagine a digital future that includes children rather than one that treats them as an exception, problem or afterthought Recognising that digital technologies are part of the infrastructure of children’s daily lives, and inspired by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), which applies from birth to 18, the Digital Futures Commission has asked what ‘good’ looks like for children in a digital world? We have sought to address and go beyond the hygiene factors of safety, privacy and security to rethink how technology can benefit children. As Baroness Kidron put it:

“So often, the digital world of children is stated in binaries – online or offline, good or bad actors, opportunity or harm. But the lived reality of children is much more complicated. At the heart of our research is what children and young people say – and they are consistent in their call: they want, need and love digital services and products, but these should be more respectful, private and safe. The Digital Futures Commission is built on the idea that there is a better digital world within our grasp. Now government and business must work to ensure that innovation is in children’s best interests.”

Working collaboratively with many experts, practitioners, researchers and, of course, children, we explored ways to design exciting possibilities for free play in digital contexts, share education data that benefit children’s best interests in privacy-respecting ways and, bringing it all together, empower innovators to make the changes children want and deserve. We tried to make our task practical by focusing on the UK, though we hope the work has wider value. And we tried to make it transparent through webinars, discussions, and blogging the progress of our work throughout. It’s been an intense three years – with a global pandemic to complicate our task, and a lot of moving parts in relation to digital innovation, policy debates and children’s lives.

Here we highlight the key outputs from our three work streams.

Playful by Design

We began with play, meaning: child-led play, free play, the right to play! Play even where adults don’t expect or want children to be. After all, childhood without play is a misery. But childhood without digital technology is unrealistic. Play in the digital world – especially play that’s about agency, experimentation, pushing boundaries, taking risks – has become the stuff of parental nightmares and tortuous policy wrangles. So, can we think afresh?

To cut through today’s anxious confusion about digital play, we took an unusual approach, grounding our work in the nature of children’s play and the value of free play in childhood. Working with Dr Kate Cowan, who reviewed the literature on free play through history and across cultures, we identified eight prototypical qualities of free or child-led play. Through consultation with children, parents and professionals working with children, we identified four further qualities. Together, these 12 qualities of play provide a language for what ‘good’ looks like for children’s free play in a digital world. With children and experts, we evaluated options for transposing the qualities of play into digital contexts, finding that the digital environment falls short on some essential qualities – intrinsic motivation, safety, risk-taking and voluntary play.

Children had plenty of ideas about how digital products could be better and, with Dr Angela Colvert, we built on their insights regarding features that enhance or hinder their play when creating our Playful by Design Tool. Centred on seven principles, this includes a range of resources to provoke reflection, discussion and fresh ideas. It is freely available for anyone involved in creating digital products used by children, and can be used by product developers and designers, whatever their experience or responsibilities, working in group settings or individually, any stage of the design process. As Jessie Johnson of the Design Council commented,

“What a fantastic resource. We’ve come across a lot of these resources. This one is exceptional! It’s been carefully curated in terms of the tool’s design process.”

Beneficial Uses of Education Data

Data are collected from children all day long – at home, in the street, during their leisure time, and while they learn at school. This data is personal, even sensitive, and can be analysed to reveal intimate details about each child. We began our work concerned that this data is too rarely shared to benefit children. But, through our collaboration with human rights lawyer, Emma Day, we quickly discovered that sharing children’s data is fraught with risk, mainly because data governance is weak. The problem is most stark at school, where children have little choice about the data being collected. Education technology (EdTech) is paid for with public funds.

Through a series of socio-legal investigations led by barrister Louise Hooper, and interviews with schools, data protection officers and other experts, led by lawyer Sarah Turner, we documented uncomfortable truths about the extensive and pervasive processing of personally identifiable data from children through EdTech. These include the unfair burden placed on schools to negotiate contracts with opaque and powerful companies, and the lack of data protection compliance of some of these companies. Also worrying are the missed opportunities to use education data to improve children’s educational outcomes. Our essay collection – including contributions from an amazing and varied range of academics and experts – explored how robust data governance could address the problems of education data processing while new approaches to data stewardship could open new possibilities for sharing education data in children’s best interests and the public interest.

In all, our series of reports diagnosed a series of problems with education data governance, which make life difficult for schools and create regulatory uncertainty for businesses. With most education data in corporate hands, data sharing for public, community or children’s benefit is impractical. Yet EdTech is big business, with the global market value of US$123.40 billion in 2022. And data processed from children while they learn enters a heavily commercial global data ecosystem with unknown future consequences.

We concluded with a blueprint for child rights-respecting data governance and practice, focusing on three priorities for the government and the regulator:

- Strengthen existing legal frameworks and enforcement to protect data about children in education;

- Introduce a 10-point certification scheme for EdTech used in school settings;

- Create a trusted data-sharing infrastructure to serve children’s best interests and the public interest.

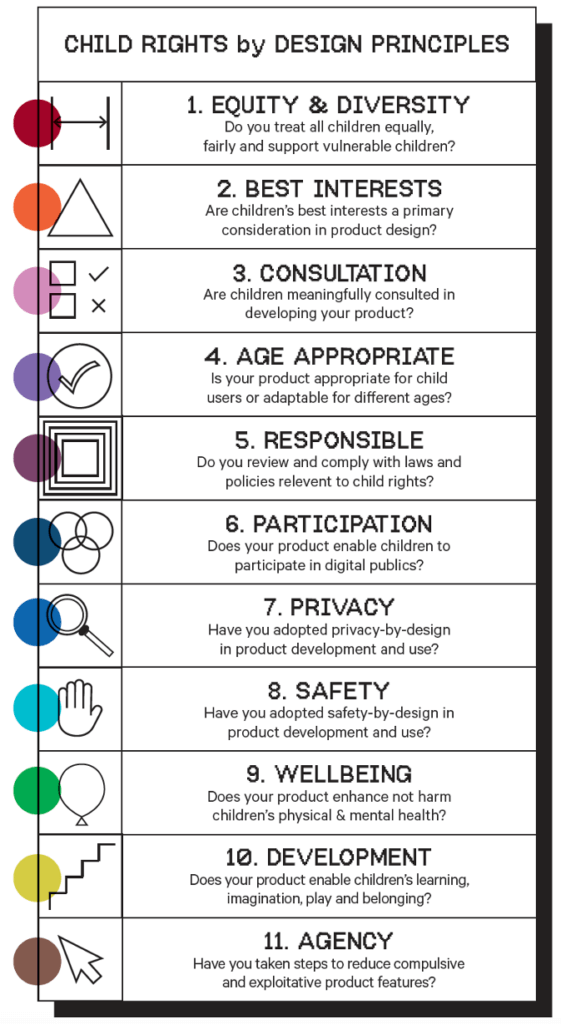

The Digital Futures Commission’s ambition is that all providers of digital products and services that impact children have children in mind and embed children’s rights into their provision. What does this mean in practice? We take our lead from the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child’s authoritative statement, General Comment No. 25, on how to implement the UNCRC in relation to the digital environment.

We consulted innovators, practitioners, experts and children to make develop the guidance and make it practical. Designers told us of their everyday dilemmas about how to consult children, meet the needs of different age groups, balance protection and participation, and know when they have got it right. To find answers for them, we drew on the collected wisdom of many rights-based, ethical and value-sensitive organisations and a consultation with children around the country.

The resulting toolkit sets out principle-based design considerations to help digital innovators embed children’s rights into digital products and services. For each principle, the guidance offers:

- An account of how specific child rights apply to digital products and services

- Distilled insights from expert sources and links to relevant legislation

- Reflections from children and young people

- ‘Stop and think’ questions to ask, mapped to the Design Council’s ‘Double Diamond’ process

- Suggested sources of design inspiration and tools.

By embedding these principles into the design of the digital environment, children’s lives will be significantly improved. As designers do not work alone, the Child Rights by Design toolkit should be included in professional training programmes – in business schools, computing, engineering and design schools. It should also be encouraged by the government, promoted by regulators, valued by investors, called for by civil society and recognised by the public. We know children will welcome it.

You can read about all of this in our Final Report. And everything is on the project website, along with our initial research agenda, our glossary of terms – produced by lawyer Ayça Atabey, who has supported our work in this and many other ways. We thank the very many people who have contributed, challenged, advised and engaged with the Digital Futures Commission in the past three years, including several thousand children and young people, as well as 5Rights Foundation, chaired by Baroness Kidron, who gave us this opportunity in the first place.

Of course, the task of embedding children’s rights in the digital environment continues. Join us to discuss children’s #DigitalFutures at our international webinar on 15th May.